Building a Deep Learning Powered GIF Search Engine

22 September 2016

They say a picture’s worth a thousand words, so GIFs are worth at least an order of magnitude more. But what are we to do when the experience of finding the right GIF is like searching for the right ten thousand words in a library full of books, and your only aide is the Dewey Decimal System?

Why we build a thesaurus of course! But where a thesaurus translates one word you know into another you don’t know, we’ll take a sentence you know, and translate it into a GIF you quite likely don’t.

The experience we’re looking for is one where a user inputs a sentence, and gets the GIF that would be best described by that sentence. This best matches the ideal of having watched every GIF on the internet, and being able to recall which one is most appropriate from memory (I swear some Redditors come quite close)

I imagined it would look something like this:

And without further ado, here’s the final result: DeepGIF

How does it work?

Overview

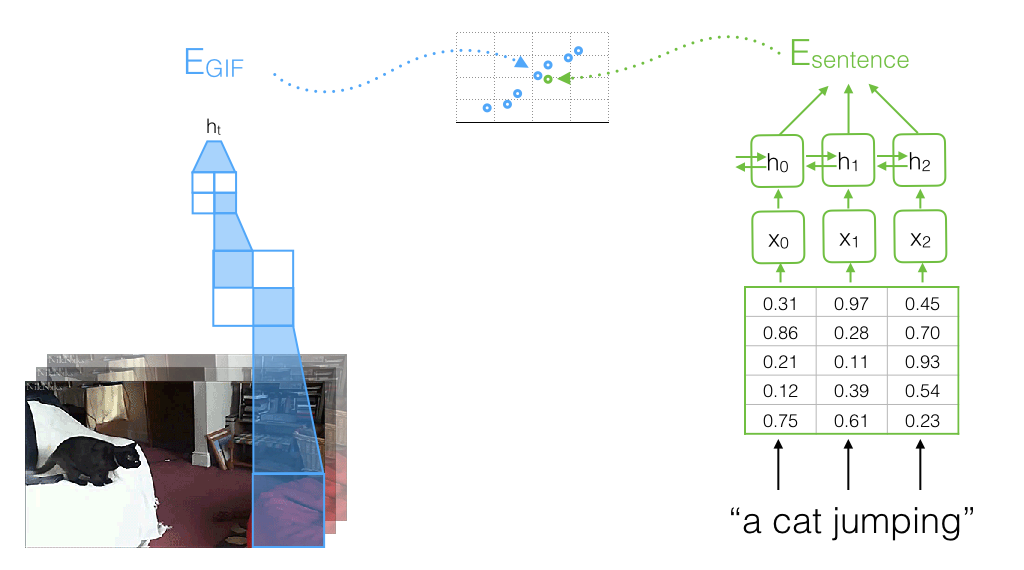

I use pretrained models and existing datasets liberally here. By formulating the problem generally enough we can get away with only having to learn a shallow neural network model that embeds the hidden layer representations from two pretrained models - the VGG16 16-layer CNN pretrained on ImageNet, and the Skip Thoughts GRU RNN pretrained on the BooksCorpus - into a joint space where videos from the Microsoft Video Description Corpus and their captions are close together. This constrains the resulting model to only working well with live-action videos that are similar to the videos in the MVDC, but the pre-trained image and sentence models help it generalize to pairings in that domain it has never before seen.

If you’re unfamiliar with much of the CNN-RNN image captioning work - there are dozens of thorough, interesting and well written posts on the specific machinery behind deep learning I will direct you to. Instead I’ll only cover how they work at a high level and how they fit together to make this GIF search engine work.

Image Classification

Like I said above, there are three pieces we put together to make this work. First, we have a convolutional neural network, pretrained to classify the objects found in images. At a high level, a convolutional neural network is a deep neural network with a specific pattern of parameter reuse that enables it to scale to large inputs (read: images). Researchers have trained convolutional neural networks to exhibit near-human performance in classifying objects in images, a landmark achievement in computer vision and artificial intelligence in general.

Now what does this have to do with GIFs? Well, as one may expect, the “skills” learned by the neural network in order to classify objects in an image should generalize to other tasks requiring understanding images. If you taught a robot to tell you what’s in an image for example, and then started asking it to draw the boundaries of such objects (a vision task that is harder, but requires much of the same knowledge), you’d hope it would pick up this task more quickly than if it had started on this new task from scratch.

Transfer Learning

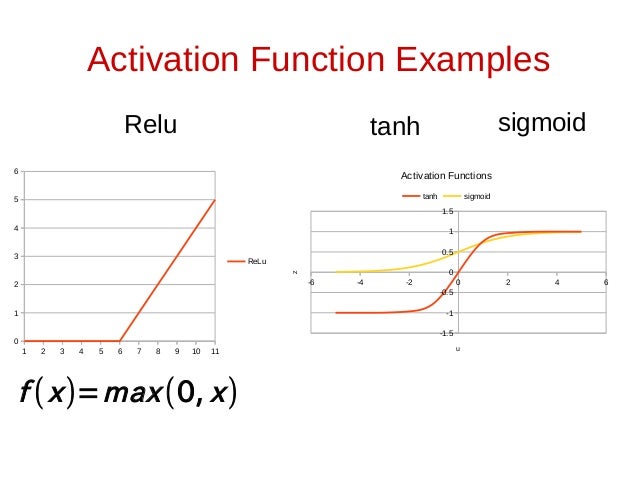

We can use an understanding of how neural networks function to figure out exactly how to achieve such an effect. Deep neural networks are so called because they contain layers of composed pieces - each layer is simply a matrix multiplication followed by some sort of function, like or or . These functions look like this

taken from (http://www.slideshare.net/oeuia/neural-network-as-a-function)

This means, for a given input, we multiply it by a matrix, then pass it through one of those functions, then multiply it by another matrix, then pass it through one of those functions again, until we have the numbers we want. In classification, the numbers we want are a probability distribution over classes/categories, and this is necessarily far fewer numbers than in our original input.

It is well understood that matrix multiplications simply parametrize transformations of a space of information - e.g. for images you can imagine that each matrix multiplication warps the image a bit so that it is easier to understand for subsequent layers, amplifying certain features to cover a wider domain, and shrinking others that are less important. You can also imagine that, based on the shape of the common activation functions (they “saturate” at the limits of their domain from , and only have a narrow range around their center when they aren’t strictly one number or another), they are utilized to “destroy” irrelevant information by shifting and stretching their narrow range of non-linearity to the region of interest in the data. Further, by doing this many times rather than only once, the network can combine features from disparate parts of the image that are relevant to one another.

When you put these pieces together what you really have is a simple, but powerful, layered machine that destroys, combines, and warps information from an image until you only have the information relevant to the task at hand. When the task at hand is classification, then it transforms the image information until only the information critical to making a class decision is available. We can leverage this understanding of the neural network to realize that just prior to the layer that outputs class probabilities we have a layer that does most of the dirty work in understanding the image except reducing it to class labels.

For classification problems like the one we just discussed, our last layer’s output needs to have dimensionality equal to the number of available classes, because we want it to output a distribution of probabilities from 0 to 1 for each of these classes (where 1 is complete certainty that the object in the image is of that class, and 0 is total certainty that it isn’t). But the layer just prior to that one contains all of the information required to make that decision (what object is in this image) and likely a bit more (it has a higher dimensionality, so unless our computer has perfect numerical precision information is being lost in the transformation to object classes).

We leverage this understanding to reuse learned abilities from this previous task, and thereby to generalize far beyond our limited training data for this new task. More concretely, for a given image, we recognize that this penultimate layer’s output may be a more useful representation than the original (the image itself) for a new task if it requires similar skills. For our GIF search engine this means that we’ll be using the output of the VGG-16 CNN from Oxford trained on the task of classifying images in the ImageNet dataset as our representation for GIFs (and thereby the input to the machine learning model we’d like to learn).

Representing Text

What is the equivalent representation for sentences? That brings us to the second piece of our puzzle, the SkipThoughts GRU (gated-recurrent-unit) RNN (recurrent neural network) trained on the Books Corpus. Like convolutional networks share their parameters across the width and height of an image, recurrent ones share their parameters across the length of a sequence. Convolutional networks’ parameter sharing relies on an assumption that only local features are relevant at each layer of the hierarchy, and these features are then integrated by moving up the hierarchy, incrementally summarizing and distilling the data below at each step. Recurrent networks however rely on no such assumption. They accumulate data over time, adding the input they are currently looking at to a history of what they’ve looked at before. In this manner, they effectively have “memory”, and so can operate on arbitrary sequences of data - pen strokes, text, music, speech, etc. Like convolutional neural networks, they represent the state of the art in many sequence learning tasks like speech recognition, sentiment analysis from text, and even handwriting recognition.

There are two interesting problems here, one is that it isn’t immediately straightforward how you represent words in a sentence like we do pixels in an image. The other is that there isn’t a clear analog to object classification in images for text. While characterizing an image as a 2D array of numbers may be somewhat intuitive, transforming sentences into the same general space won’t be. This is because while you can easily treat the brightness/color of a pixel in an image as a number on some range, the same doesn’t seem as intuitive for words. Words are discrete while the colors of pixels are continuous.

Discrete vs Continuous

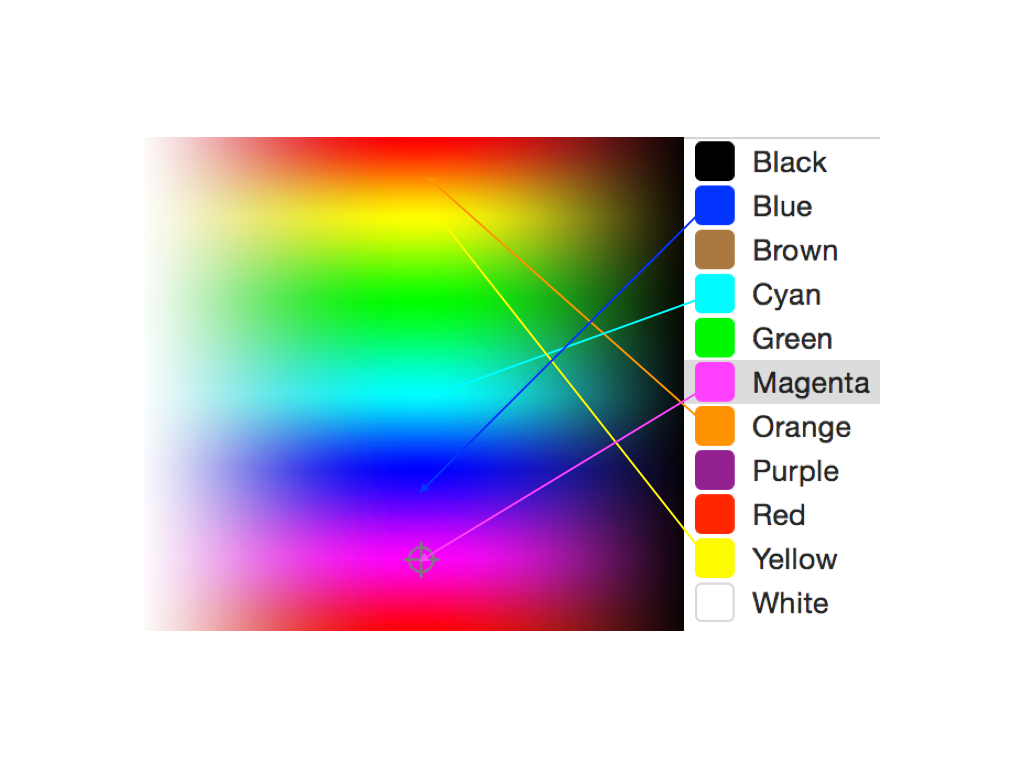

What does this mean? Roughly, it means that the space is fully occupied - there is always a value in between some other values. Take two different color values for a pixel; there is always a color value in between them. We can’t say the same for words. Where there are infinitely many colors “between” [blue-green block] and [yellow-green block], we can’t say the same for the words between “dog” and “cat”. Now note, this doesn’t mean that having more words would make it continuous (though it does help bridge the gap) - it just means that the words are distinct from one another, like categories.

I like to think of the difference somewhat like that between buttons and dials on a boombox. There are some inputs that just make more sense as buttons than dials (on vs off, radio tuner vs auxiliary input mode, etc.) and some make more sense as dials than buttons (volume, frequency, bass level, etc.).

Importantly (and necessarily for our application), these definitions aren’t as incontrovertible as they may seem. While the words themselves are certainly distinct, they represent ideas that aren’t necessarily so black and white. There may not be any words between cat and dog, but we can certainly think of concepts between them. And for some pairs of words, there actually are plenty of words in between (like the word warm between hot and cold).

Back to colors, the space of colors is certainly continuous, but the space of named colors is not. There are infinitely many colors between black and white, but we really only have a few words for them (grey, steel, charcoal, etc.). What if we could find that space of colors from the words for them, and use that space directly? We would only require that the words for colors that are similar are also close to each other in the color space. Then, despite the color names being a discrete space, for any operations we want to do on or between the colors we can convert them to the continuous space first.

Word Vectors

Our method for bringing the discrete world of language into a continuous space like images involves a step exactly like that. We will find the space of meaning behind the words, by finding embeddings for every word such that words that are similar in meaning are close to one another.

Our friends over at Google Brain did exactly this, with their software system Word2Vec. The realization key to their implementation is that, although words don’t have a continuous definition of meaning we can use for the distance optimization, they do approximately obey a simple rule popular in the Natural Language Processing Literature

The Distributional Hypothesis - succinctly, it states :

“a word is characterized by the company it keeps”

At a high level, this means that rather than optimizing for similar words to be close together, they assume that words that are often in similar contexts have similar meanings, and optimize for that directly instead.

More specifically, the prevailing success was with a model called Skip-grams, which tasked their model with directly outputting a probability distribution of neighboring words (not always directly neighboring, they would often skip a few words to make the data more diverse, hence the name “skip grams”). Once it was good at predicting the probability of words in its context, they took the hidden layer weight matrix and used it as a set of dense continuous vectors representing the words in their vocabulary.

Once this optimization has been completed, the resulting word vectors have exactly the property we wanted them to have - amazing! We’ll see that this is exactly the pattern of success here - it doesn’t take much, just a good formulation of your objective, and tools sufficient to get you there. The initial Word2Vec results contained some pretty astonishing figures - in particular, they showed that not only were similar words near each other, but that the dimensions of variability were consistent with simple geometric operations.

I.e. you could take the continuous vector representation for king, subtract from it the one for man, add to that the one for woman, and the closest vector to the result of that operation is the representation for queen.

That is the power of density, by forcing these representations to all be close to one another, regularities in the language become regularities in the embedded space. This is a desirable property for getting the most out of your data, and is generally necessary in our representations if we are to expect generalization. When generalizing to a new example is as simple as linear interpolation, then your model is much more likely to exhibit it of course.

Sentence Vectors

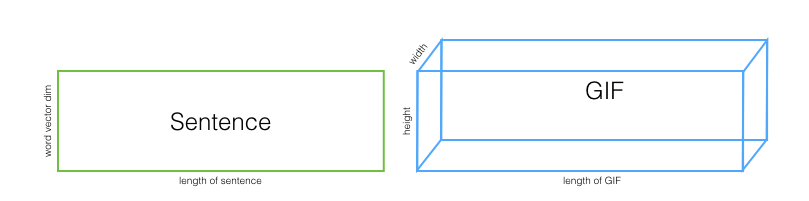

Now that we have a way to convert words from human-readable sequences of letters into computer readable sequences of N-dimensional vectors we can consider our sentences as arrays too - with dimensions: dimensionality of the word vectors, and length of sentence.

This leaves us with our sentences looking somewhat like rectangles, with durations and heights, and our GIFs looking like cuboids / rectangular prisms, with durations, heights, and widths.

Just like with the CNN - we’d like to take an RNN trained on a task that requires skills we want to reuse, and isolate the representation from the RNN that immediately precedes the specificity of said task. There are many classical natural language understanding tasks like sentiment analysis, named entity recognition, coreference resolution, etc. but surprisingly few of them require general language understanding. Often, classical NLP methods that pay attention to little more than distinct word categories do about as well as state-of-the-art deep learning powered systems. Why? In all but rare cases, these problems simply don’t require much more than word level statistics. Classifying a sentence as positive or negative sentiment is roughly analogous to classifying whether an image is of the outdoors or indoors - you’ll do pretty well just learning which colors are outdoors/indoors exclusive and classifying your image on that alone. For sentiment analysis, a simple but surprisingly effective method amounts to learning negative/positive weights for every word in a vocabulary, then to classify a sentence just multiply the words found in that sentence by their weights and add it all up.

There are more complex cases, that require nuanced understanding of context and language to classify correctly, but those instances are infrequent. What often separates these remarkably simple cases from the more complex ones is the independence of the features: simply weighting words as negative or positive would never correctly classify “The movie was not good” - at best it would appear neutral when you add up the effects of “not” and “good”. A model that understands the nuance of the language would need to integrate features across words - like our CNN does with its many layers, and our RNN is expected to do over time.

While the language tasks above rarely depend on this multi-step integration of features, some researchers at the University of Toronto found an objective that does - and called it Skip-Thoughts. Like the skip-grams objective for finding general word embeddings, the skip-thoughts objective is that of predicting the context around a sentence given the sentence. The embedding comes from a GRU RNN instead of a shallow single hidden-layer neural network, but the objective, and means of isolating the representation, are the same.

Learning a Joint Embedding

We now have most of the pieces required to build the GIF search engine of our dreams. We have generic, relatively low dimensional, dense representations for both GIFs and sentences - the next piece of the puzzle is comparing them to one another. Just as we did with words, we can embed completely different media into a joint space together, so long as we have a metric for their degree of association or similarity. Once a joint embedding like this is complete, we will be able to find synonymous GIFs the same way we did words - just return the ones closest in the embedding space.

Although it is conceptually simple, learning this embedding is a significant challenge - it helps that our representations for both GIFs and sentences are dense but they are only low dimensional relative to the original media ( ~4K vs ~1M ). There is an issue fundamental to data analysis in high-dimensional space known as the “curse of dimensionality”

The Curse of Dimensionality - from Wikipedia :

The curse of dimensionality refers to various phenomena that arise when analyzing and organizing data in high-dimensional spaces (often with hundreds or thousands of dimensions) that do not occur in low-dimensional settings such as the three-dimensional physical space of everyday experience… The common theme of these problems is that when the dimensionality increases, the volume of the space increases so fast that the available data become sparse. This sparsity is problematic for any method that requires statistical significance. In order to obtain a statistically sound and reliable result, the amount of data needed to support the result often grows exponentially with the dimensionality. Also, organizing and searching data often relies on detecting areas where objects form groups with similar properties; in high dimensional data, however, all objects appear to be sparse and dissimilar in many ways, which prevents common data organization strategies from being efficient.

You can think of our final set of parameters as statistical result that requires significant evidence, each parameter update proceeds according to the data we present our training algorithm. While with a dense dataset this would mean each parameter update is likely to be evidenced by many neighboring data points, sparse high dimensional data makes that exponentially less likely. Thus we will need to ensure we have sufficient training data to overcome this burden.

We’ve formulated our problem as one of associating GIFs with their sentence descriptions, but this isn’t exactly a well trodden path - I searched and searched for a dataset specific to this to no avail. GIPHY.com is closest - with a substantial trove of GIFs, and they all have associated human labels, but the labels are rarely of the contents of the image itself - instead they are often tags regarding popular culture references, names of people/objects, or general emotions associated with the imagery. By recognizing that we could focus on live action GIFs - which are just short, low resolution videos - I found the Microsoft Research Video Description Corpus, a dataset of 120k sentence descriptions for 2k short YouTube video clips.

In the Skip-Thoughts paper they show that their model returns vectors that are sufficiently generalizable that they can demonstrate competitive image-sentence ranking (a very similar task to ours, just with static images instead of GIFs) with a simple linear embedding of both image and sentence features into a joint 1000 dimensional space. Thus, we attempt to replicate those results but with the YouTube dataset. Our model will be assembled such that there are two embedding matrices, one from the image representation and one from the sentence representation, into a 1024 dimensional joint space. There will be no non-linearities, in order to prevent excessive loss of information. When learning a model, we need to know what makes a good set of parameters and what makes a bad one, so we can appropriately update the parameters and get a better model at the end of our learning process - this is called our “objective function”.

Typically in supervised learning we know the exact correct answers that our model is supposed to be outputting, so we can directly minimize the difference between our model’s outputs and the correct answers for our dataset. In our case here, we don’t know exactly what the embedded vectors in this low dimensional space should be, only that for associated GIFs and sentences the embeddings should be close - and we don’t want them to be exactly the same numbers either because there are multiple possible associations for every GIF and our model will probably end up drawing stronger conclusions than it should. We can accomplish this objective with a formulation called max-margin, where for each training example we fetch one associated pair of GIFs and sentences, and one completely unassociated pair, then optimize the associated ones to be closer to each other than the unassociated ones. We do this enough times (~5M times to be exact) and we have a model that accurately embeds GIFs and the sentences that describe them near one another.

Turning it into a real service

The technical side of actually getting this working is both completely unrelated in content to this post and sufficiently involved that it deserves a post of its own, but in short I run the service on AWS g2.8xlarge GPU instances with some clever autoscaling to deal with variable load. I also obviously can’t compete with a service like GIPHY on content, so instead of managing my own database of GIFs I take a hybrid approach where I maintain a sharded cache across the instances available, and when necessary grab the top 1k results from GIPHY, then rerank this entire collection with respect to the query you typed in. When you type a query into the box at http://deepgif.tarzain.com the embedding process described above is run on your query, while most of the GIFs’ embeddings have all been precomputed - if there are precomputed, cached GIFs with a sufficiently high score then I return those results immediately, otherwise I download some GIFs from GIPHY, rerank them, and return relevant results.